Neck pain and work

Many people consider that their neck and back problems are due to the demanding nature of their job. Perhaps because they sit at a computer all day, or because they turn their head a lot in doing their job.

It's a common and expensive question: does work cause spinal problems?

We doctors and researchers haven't answered the question well at this stage. The question has been around for about 50 years, since workers' compensation became a common way of dealing with musculoskeletal problems.

The research is hard to find, difficult to read and complex to assimilate.

Why is it difficult to answer this question?

First up, many of the studies are not the right kind of research. Typical studies undertaken to assess whether work causes neck pain are cross-sectional in design. A cross-sectional study takes a snapshot at one point in time. For example, people may be asked, “Do you have neck pain?” or “Have you had neck pain in the last year?” The same person will be asked other questions, such as about their age, their work history, and involvement in other activities such as sport.

The difficulty with this type of study is that people's memory is influenced by many factors.

For example, a receptionist with a sore neck, who could still do their job and had one or two massage treatments, may not remember a neck problem from five years ago.

However, a labourer with the same neck problem may not have been able to unload containers day in day out. With three months off as a consequence, the labourer is more likely to remember their episode of neck pain. This is known as recall bias, and is a significant problem with cross-sectional studies.

The second issue is what are we measuring? Different studies have measure different outcomes.

Are we assessing the level of ‘wear and tear’ on x-rays, or whether someone reports pain? Or are we measuring consequences of the pain such as time off work, health-seeking behaviour etc?

Thirdly, when we ask someone about what job they do, it doesn't necessarily tell us what body movements are involved. For example, a picker and packer might be picking light orders such as small plastic components. Alternatively, they may be repeatedly picking heavy items, such as 25 kg boxes of drink bottles.

To answer the question about work and neck pain we need more thorough study designs. Studies needs to follow a large number of people over many years and have a rich understanding of the actual physical demands of the work. These studies have not been done, or at least not done well enough to answer the question definitively.

But what do we know?

Professor Charlotte Leboeuf-Yde is a researcher who’s looked at this area with a sharp eye and a critical mind. She spent much time looking at the research available in order to summarise the results.

Charlotte visits Australia from time to time and has presented some of the knowledge she has gained to occupational physicians. Here’s some of that information.

In terms of neck problems, Charlotte points out there is limited but fairly consistent evidence for an association between cervical degeneration (wear and tear of the neck on x-rays) and:

- extremely repetitive movement of neck over a long time; and

- prolonged heavy axial cervical strain.

However, degeneration seen on neck x-rays follows a very different pattern from neck pain.

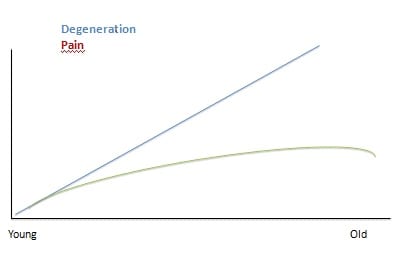

The likelihood of having degeneration on neck x-rays increases with advancing age. There is a very strong linear link between degeneration on x-rays and a person's age. The graph looks something like this:

The vertical axis shows the likelihood of degeneration on x-rays (between 0 and 100%) and the horizontal axis shows a person is age (young to old).

But the likelihood of a person reporting neck pain does not increase in the same way. The green line in the graph below shows the likelihood of a person reporting neck pain. In fact, the percentage of people reporting neck pain increases until about the age of 40, and then decreases. Very different to the pattern of degeneration with age.

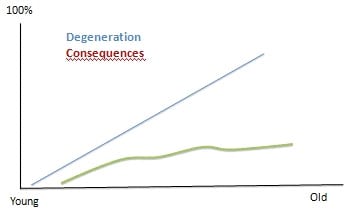

Further, the consequences of having neck pain, such as seeking treatment for the condition or having time off work, don't follow the pattern of degeneration.

We’ll now look at more sophisticated graphs that show actual information collected from surveying large numbers of people.

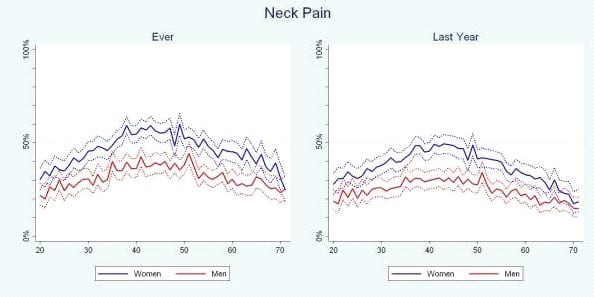

The first graph below shows the percent of people surveyed who reported they have ever had neck pain (graph on the left) or had neck pain in the last year (graph on the right).

Women are represented by the solid blue line, and men by the solid red line. The dotted lines measure the 95% confidence intervals, which is a complex issue to understand but essentially means you can be 95% confident that the results lie between the dotted lines.

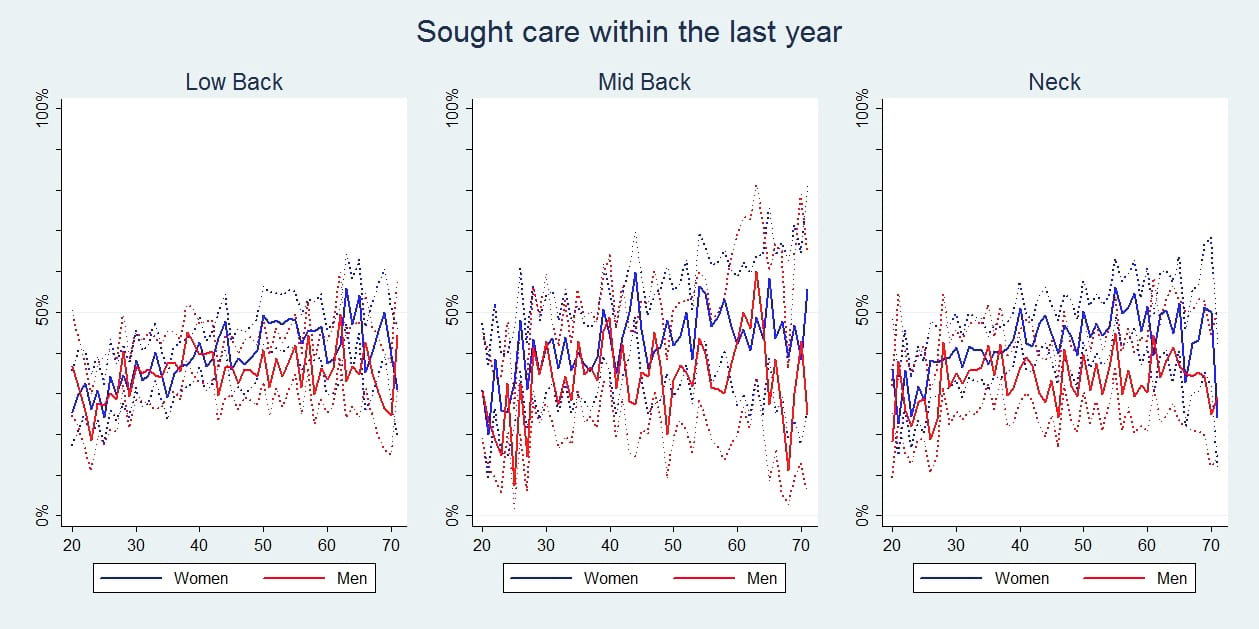

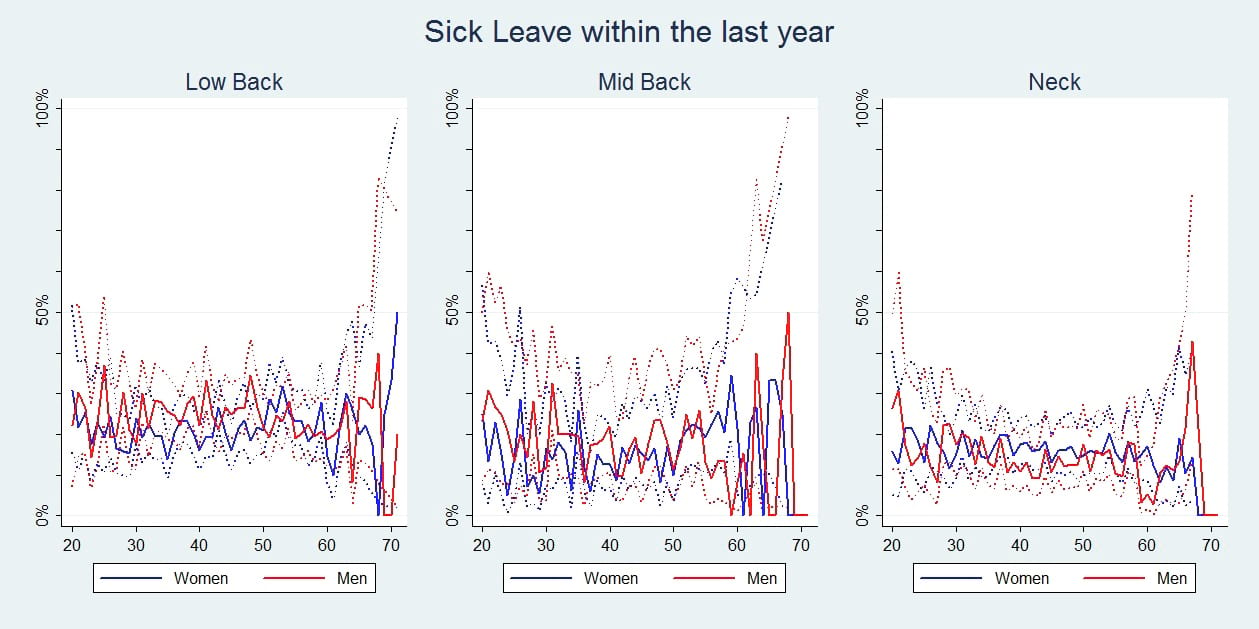

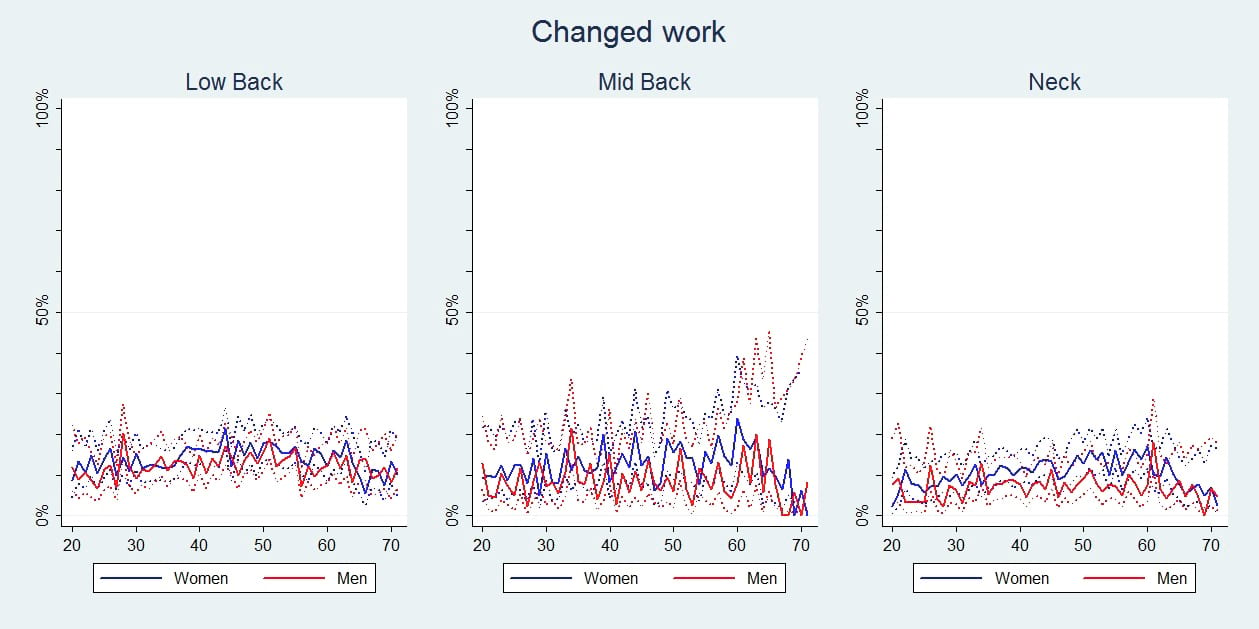

The next three graphs show men and women in the same graph - and demonstrate:

- health seeking behaviour;

- time off work; and

- whether someone has changed their job because of low and mid back pain and neck pain.

Once again, focus on the solid lines rather than the dotted lines.

For neck pain there is some increase in health seeking behaviour as a person ages, but sick leave and changing work because of neck pain does not increase over time.

What does all this information tell us?

It tells us that neck pain doesn't increase as we age. The likelihood of having of neck pain increases to about the age of 40, and then decreases over time.

If wear and tear caused neck problems you'd expected it to increase over time. You'd expect labourers aged 60 to report higher levels of neck pain that 30 or 40-year-olds.

The big picture seems to suggest that work is not a major factor causing neck problems. A large amount of repetitive neck movements is associated with an increase in degeneration on x-rays. But degeneration doesn’t correlate well with patterns of the likelihood of neck pain, sick leave or changing jobs.

Other studies have shown that genetics plays a large role. It may be that work contributes to some neck problems, but the evidence regarding this is weak and limited.