Divided data does not conquer in NSW

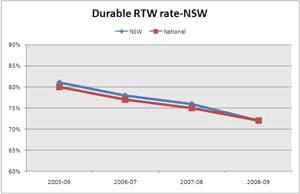

In NSW durable return to work (RTW), a measure of sustained return to work, has steadily declined over the last three years. Durable RTW has dropped from approximately 80% to 72%, tracking the national average.

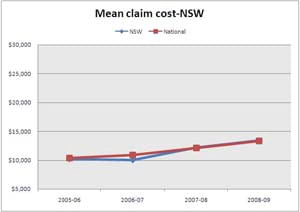

Claims costs are rising.

The number of days off work has traditionally been lower in NSW than across Australia generally. However, ‘days off’ in NSW has risen from just over 30 to 50 days on average per claimant over the last two years, according to the scheme data provided to the Return to Work Monitor.

We talked to people working in RTW in New South Wales and from their perspective there is nothing anomalous about the state’s slump in RTW results.

The consistent message, from those in the know, is that the lack of a centralised database of RTW information in NSW is preventing transparent assessment of performance and therefore also preventing the state from identifying and dealing with problems effectively.

In fact, NSW’s system has in-built accountability issues. In most Australian jurisdictions the WorkCover regulator has access to all claims data. However, in New South Wales the data is not housed centrally but is instead held by the insurer, and then passed on to WorkCover.

Why does it matter who holds the data?

Firstly, if you don’t have a clear and reliable picture of what is happening across the system, it’s hard to develop sensible policy. You can’t manage what you can’t measure. And you certainly can’t adopt a coherent approach to problem-solving if you can’t pinpoint the problems.

Secondly, the lack of a centralised database opens the system up to distortion. As things stand, WorkCover NSW relies on those it regulates for the information with which it makes its regulatory decisions, including performance-based financial incentives for insurers.

This means that there is a potential for insurers to massage data, selectively passing on information favourable to their chance of being paid higher amounts for good outcomes. Such abuses are probably rare, but the lack of transparency in data collection allows for them and we are advised that they do occur.

Lack of clear data also makes it difficult for the regulator to understand what is happening at the micro level of case management. An example cited to us was a rehabilitation provider being engaged by an insurer to manage return to work. As part of their deal, the insurer agreed to pay the rehab provider $5000 if the worker was at work at specific points in time, leading to several payments being made throughout the course of the case.

Because of the decentralised system, such excesses and anomalies take time and energy to identify and deal with. In such a context other providers who are playing by the spirit as well as the rules of the game become more cynical. The regulator’s attention is also focused on micro problems, rather than macro solutions.

In a low trust environment, individuals and organisations spend more time and money on compliance and protecting themselves from being exploited. Innovation is stifled. Formal arrangements are needed to enforce agreements. Organisational contracts between a regulator and contractors where agreements are difficult to monitor have less success.

Recognizing that there are problems in the system, the authority endeavours to rectify them. Band-aid solutions, tackling only part of the problem, may work, but our NSW colleagues tell us they are often making the situation worse.

A recent change has been to place constraints on insurers in obtaining independent medical opinions. This is causing substantial delays in trying to manage problem cases, further demoralising claims agents and employers. Early coordinated management of employees not working within the spirit of return to work care is vital for the system’s integrity. Stopping overuse of independent medical assessments is appropriate but doing it in a way that hampers effective case management is not.

There is a significant lack of awareness about return to work management at the employer level. Return to work is often outsourced to rehabilitation providers. Return to work coordinators in New South Wales are trained through a mandatory two-day training program but workplace rehabilitation seems too hard, and is not undertaken to the same extent as in many other jurisdictions.

Anecdotally, we were also told that medical over-servicing occurs, included allied health and surgical over-servicing. This is a major concern for the wellbeing of patients, with over-servicing including unnecessary operations and continued passive treatment that fosters disability rather than ability.

In short, those that work within the system consider it is without integrity. Some use the word corruption, others not prepared to go that far. Yet the definition of corruption is impairment of integrity, virtue, or moral principle, and the NSW system meets that definition according to those who have provided input for this article.

How does one fix a broken system? Getting access to quality information and understanding how the system is working is a key element and a centralised database is the only way that can reliably occur.

Partnership cannot work without a system having integrity. Acknowledging the depth of the issue is a start.